Radical Listening as a Colonial Remedy in Indonesia and Madagascar

Interview with

Nina Finley

Research Manager at Health in Harmony, US

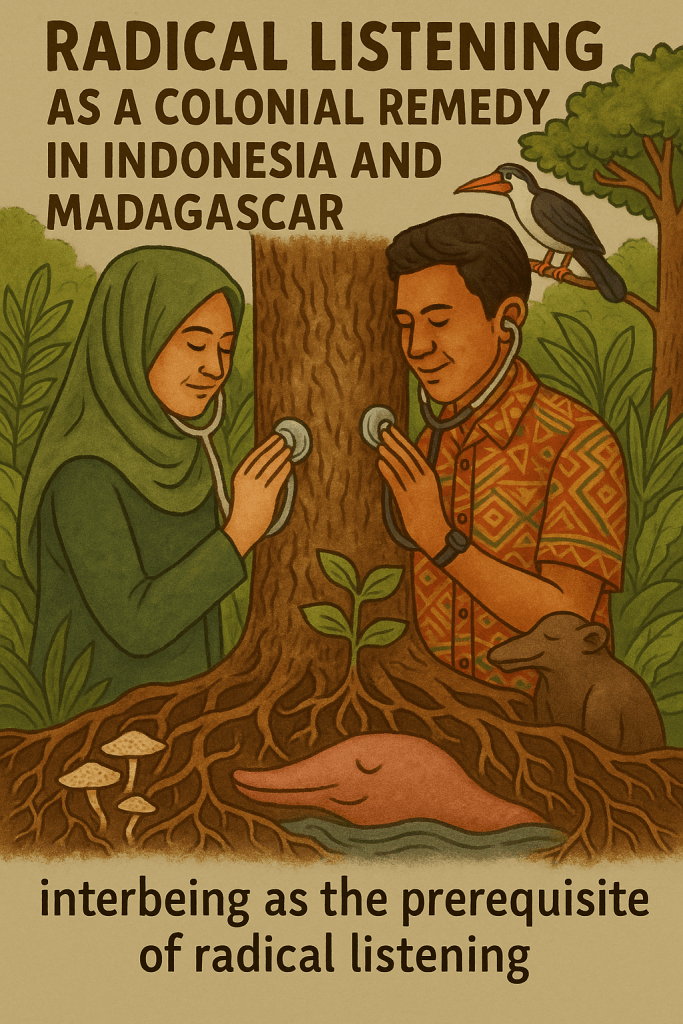

“The core value of radical listening is interbeing. So, there’s this concept of interbeing that was forwarded by a Vietnamese Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh. And it says not just that I depend on you, and you depend on me, which is true, but really that I am you and you are me. It’s that sense that. If I am not thriving, then you on the other side of this microphone are not thriving, but also people I’ve never met on the other side of the world aren’t truly thriving because we’re all so deeply connected.”

“Those who work for the NGOs often think of the communities as the benefactors. But the reality is, the communities are the ones who are keeping carbon out of the atmosphere, who are regulating our climate, who are preventing pandemics, who are protecting biodiversity from extinction, and the rest of the world, those of us like me who live in cities who can’t do that myself. We’re benefiting. We are the beneficiaries of their work that they’ve been doing in some cases for millennia in the same forest. […] We’re working a lot at Health and Harmony to try to get this ethos, the radical listening, interbeing, and anti-colonial ethos absorbed across the fields of healthcare, climate change, and development Organizations.”

—Nina Finley

Radical Listening is about Flipping the Colonial and Neo-colonial Power Paradigm

Angie: Since we’ve been talking about the conservation practices and project implementation, would you say that the voices of indigenous peoples and rainforest communities in the global South are often silenced due to a long history of colonization and racism that continues to reject local expertise?

Nina: I think you said it well. A lot of the ways that a development science, research, climate change carbon projects are conducted is very colonial and is a legacy of the metropole-colony dynamic that was set up over the past 500 years of European colonialism across most of the world. It’s embedded in the way a lot of systems work. It’s embedded in the way a lot of resources are distributed, and it’s embedded in the way that a lot of people who are trained in the global north, or as it’s sometimes called in the global minority regions of the world, colonizing power regions are trained to consider knowledge emanating from those parts of the world as higher and expertise is emanating from the type of Western academic accolades or professional accolades that we’re used to seeing valued. So that’s where I think radical listening does a really nice job of flipping that paradigm on its head. At the heart of radical listening is that it requires us to recognize that the expertise to get us out of the climate emergency lies with the indigenous peoples and local communities. They are the experts; they are the ones who have the solution. And we need as a global community to stop ignoring that and centre that expertise.

Another way of valuing indigenous expertise is through rematriating these resources, that is a word I learned a few months ago from an excellent organization called Indian Collective. It’s about reciprocity, trying to return some of these resources that have been stolen through colonialism, directly to indigenous peoples and local communities. A lot of the ways that funding streams are returned right now is through grants and funding that have a lot of restrictions or expectations, a huge burden of reporting. But just with the understanding that the communities are the experts, so they don’t need their funding to be restricted by someone else who thinks they know better. They just need these resources rematriated so that they have the flexibility to then protect their forests and be the leaders that teach the rest of us where we need to go.

The Rematriation of Resources to the Indigenous Communities

Angie: Thank you for explaining how HIH not only subvert colonial and neocolonial power dynamic through radical listening, but you also seek to rematriate these resources. Could you explain further on how indigenous-led funds work?

Nina: I want to just share a quote from Claudia Suarez, she’s an indigenous thinker and leader, and she said, “we indigenous people are risking our lives to be the guardians of the forest. If you trust us to guard the trees.” There’s no reason to not also trust us to guard the finances. So she’s picking up on this sense that there is this growing understanding, though still nascent, that yes, Indigenous peoples are the experts, but we have to be really on guard that then doesn’t get translated into an extraction of indigenous knowledge and further impoverishment or extraction or theft from Indigenous people who are people with land and needs and bodies who need resources to live and need rights for their lands and need protection for those rights.

Where Health in Harmony is moving at scale is towards working with indigenous led funds. So right now, less than 1 percent of climate finance from the United States is going into indigenous communities, less than 1%. When we know that these communities are doing the absolute most frontline labor to protect ecosystems and carbon, we need to move the needle and get it up from 1 percent to what 5, 10, 30, 50 percent of the money, not going through big NGOs or corporations, but just directly to these communities. And some of the feedback we’ve been getting from the indigenous led funds is they need data. They need to be able to make the case to the big funders and decision makers of the world that they are the ones doing the most to protect carbon as well as biodiversity and health. And get the resources that are pledged at the big climate events like the cops billions of dollars being pledged to climate change and then not really having anywhere to go. We need to get these into the hands of indigenous communities. To do that, we need to publish data showing their impact.

We are working very closely with one called Pawanka, that’s an international indigenous led fund that works across the global south or the global majority in all the different sociocultural regions of the world. This is a strong movement of a financial mechanism where large resources can be funneled directly to indigenous communities through a mechanism, a fund that is itself indigenous led. This is a big step towards anti colonial rematriation of resources. These indigenous led funds are very grassroots.

Non-Hierarchical Relationship-Based Conservation Model

Angie: I hope that we can move into discussion on the anti-colonial ethics behind your organization’s reforestation projects. The fact that many communities in Indonesia suffer from extreme poverty and that the forests have become degraded is largely indebted to a long history of colonial and neocolonial exploitation that continues to take resources from indigenous communities while neglecting the value of their well-being. For instance, in Amitav Ghosh’s The Nutmeg’s Curse, he described how the Dutch East Indian Company, who dominated the spice trade at the time, massacred the Bandanese for the sake of securing nutmeg as valuable commodities. So how does working on reforestation, providing healthcare and education, address the historical systemic injustices?

Nina: To understand colonialism and the impact of this exploitation and theft, you really must understand the local as well as the global and specifically what happened in Indonesia is both the same as what happened everywhere across the world and very particular to that.

The colonial process is fundamentally about outsiders and determining what’s best and taking. So, if you flip that, it’s about outsiders in this case saying, we don’t know best, you know best. What is that? What is best? And then reciprocating and rematriating some of those resources rather than extracting. And fundamentally, I think colonialism is based on a hierarchical understanding that there are people who deserve and people who don’t, or there are people who know and people who don’t, right? It’s based on racism. It’s based on these systems of injustice. Whereas what we do at Health and harmony is all based on interbeing and the understanding that there is no charity involved.

Incorporating Qualitative Monitoring Techniques and Storytelling as indicator of Healthy Community

Angie: You pointed out that quantitative analysis is, although important, not the only way of measuring the successful implementation of a project. I’m curious, what are some of the qualitative indicators that a community is healthy and thriving?

Nina: Years ago, we started down this path, asking ourselves at Health in Harmony, How do we measure community thriving? How do we ask communities if they want to, how they want to measure their own thriving? And of course, we started with the wrong idea. We started with quantitative indices that would measure it on a numerical scale. I was in meetings in Indonesia asking communities; we asked, “How would you rank your community? How would you measure this?” And the answers were very humbling. They said, “we wouldn’t rank ourselves from one to five.” And community leaders again and again told us, we measure this with stories. We measure our history, our future, and our knowledge with stories, some of which can be public, some of which are very private.

And that’s how we do it. So, we pivoted, and this is the case with almost every idea that has come from an academic or a member of the global staff or the global north. It’s not right at first, so you need to listen, and the right way to monitor and the right way to implement a program comes through radical listening from the communities. Again, this has happened, and now we’re very much being guided by that wisdom, and we’re working on community participatory videography.

If there’s a desire to make a story publicly, it can be shared. But if there’s a desire to make a video to preserve in turn, and not share it, that’s also possible. And once communities have the equipment and they make their own participatory videos, it’s up to them what they use it for. One of the stories I heard from one of our partners who does this is that the videos were used to stimulate further conversation in the community. So, the videos were created by the cohort and then shared on the screen. Everyone in the community. Political advocacy pack for advocating for their own land rights, and the video really spurred forward and led into developing solutions. So, keep your eyes out for community participatory videography coming soon, but I’m excited.

Replicating Radical Listening Principles in Madagascar

Angie: I learned from WHO’s newsroom article, Regenerating Rainforests in Madagascar by Listening to Communities, that HIH is currently replicating your conservation model in Indonesia to work with communities in Manombo Rainforests in Madagascar. Why did your organization select this specific project site? And does the principle of radical listening work well in a different geographical region?

Nina: We choose Madagascar for a couple of reasons. One, it has incredible biodiversity that you couldn’t find anywhere else on Earth. And it’s also been deeply impacted by colonization and deforestation. It only gained independence from France’s rule in 1916 and had already lost two-thirds of its forest to extraction by French timber and the ramifications of colonialism that are also seen through people being displaced and farming practices being disrupted.

We really need to conserve the forest there. And it also has some of the highest malnutrition and the highest poverty of any country in the world that is not an active war zone. And this is all very intertwined, right? When people are struggling to feed themselves, they’re much more likely to overextract from the forest out of a need to survive, whereas when people are healthy and well fed, they’re much more likely to protect the forest for future generations, for their kids, for the wildlife, and for their own ecosystem services, like water, clean air, and temperature regulation.

Broadly speaking, the deforestation that we saw in Indonesia is caused by selective logging, with individuals taking out large hardwood timber trees like ironwoods and selling them for cash on an illegal timber market for healthcare. In Madagascar, it’s quite different. There isn’t a strong international timber market, and there aren’t these huge hardwoods like you would find in Borneo. So rather than logging for cash, we’re seeing a lot more slashed and burned encroaching deeper and deeper into the forest.

We’re seeing wild food harvesting in the forest, so digging of wild tubers during what’s called the hunger season between harvests sometimes trapping and hunting animals such as birds, bats, and mammals for food consumption. Other than that, communities sometimes cut trees to build houses, especially after cyclones when houses have been destroyed. We see a surge into the forest trees for rebuilding materials.

I have worked with the programs team there that is there earlier this year in October and the level of trust between the communities and the staff is strong. It’s just a powerful collaboration. And we just ask communities what the solution is for each and then invest in those. The region that we’re working around has not continued to lose tree cover. Since we started this partnership, we’re holding steady and little by little starting to increase that for us with reforestation projects. They’re a bit slow going because of the soil being depleted and droughts, but we have a lot of projects going to try to ameliorate that. So yes, Radical Listening does work in a different geography, so we feel confident in working with communities across rainforests going forward.

We need Collective Action to Change Systems and Move Resources

Angie: Thank you. And we’re reaching the end of our interview today. The final question I have for you as well as for myself is how can understanding these connections between forest ecosystem and human health, as well as the colonial history that shape tropical forest landscape, remind us of our shared responsibility to protect them and safeguard our planet’s climate future.

Nina: I believe we need a paradigm shift in our understanding of connection, followed by the mechanisms to act on that new knowledge. We must take responsibility for our multi-species kin around the world. We are, to some extent, trapped within a system that relies on fossil fuels, imports commodities that drive deforestation, and strips land rights from indigenous people. We’re embedded in this system, and opting out is virtually impossible.

But what gives me hope is that opting out isn’t the solution. We can’t fully escape the system or live a life without waste or fossil fuel emissions. That idea, I believe, is a myth—a falsehood perpetuated by corporations and fossil fuel industries. The notion that individual action or striving for individual perfection is the answer is misleading. We’re often sold this idea—don’t use straws to save sea turtles, carry a canvas bag, avoid plastic. I’m not saying we should use more straws or plastic, but these actions, though worthwhile, are individual and don’t lead to the collective change we need.

Sometimes, corporations and other influential entities mislead us into thinking that individual actions are the key and that it’s up to us to feel guilty or proud based on our personal choices. But we must move beyond this mindset. Individual actions, no matter how well-intentioned, have never solved collective problems on their own. What truly makes a significant impact is collective action—working together to change policies, systems, and resource distribution, and making changes at the community level.

At Health in Harmony, we focus on creating the links for people who want to support rainforest communities. Most people don’t have a way to directly send resources to indigenous communities—whether individually or through corporations. A big part of our work is developing financial mechanisms that make this possible. We want to ensure that anyone who understands their interconnectedness with these communities has the tools to act. This is part of a broader paradigm shift, where resources and expertise are redirected toward indigenous communities, away from those who are responsible for creating the problems in the first place.

Concluding Remarks

Nina, thank you for sharing your experiences collaborating with indigenous communities in Indonesia, Madagascar, and Brazil, as well as your passion for restoring tropical forests. In this episode, we’ve explored the impact of colonialism and how it has dispossessed indigenous people of their land, fragmenting their connection to the more-than-human world.

We also discussed how radical listening and rematriation can address historical injustices by empowering indigenous communities to conserve and restore forests based on their traditional ecological knowledge. I hope that more NGOs will adopt your approach to support forest-dependent communities in creating non-hierarchical, community-driven solutions to tackle the global climate crisis.