Safeguarding Planetary Health: A Community-Driven Conservation and Health Exchange Initiative in West Kalimantan, Indonesia

Based on the Interview with Muhamad Rusda Yakin, ASRI’s Forestry Manager

In the village of Penjalaan, nestled at the forest’s edge in West Kalimantan, Karim used to wake before sunrise to prepare his chainsaw. For years, the forest was his livelihood—one tree at a time, felled to feed his family, though the hunger never fully left. The irony cut deeper than the chainsaw’s teeth: after clearing hundreds of trees, he still lived in a fragile wooden house, its walls thin against rain and time.

In 2018, everything changed. Karim placed his chainsaw into the hands of the very people once seen as obstacles to survival—ASRI’s team of conservationists and health workers. Through the chainsaw buyback program, he received not only a modest fund but something less tangible and more enduring: a new path. He began farming, raising chickens, and later expanded to fishing. Today, his business flourishes. His home stands stronger. And Karim? He’s now a forest guardian, collaborating with ASRI’s forestry team in protecting the very ecosystem he once helped dismantle.

His story is not an exception—it’s part of a growing mosaic of change that challenges how we think about conservation, livelihood, and justice.

Graphic Illustration of the Chainsaw Buyback Program

In Aceh province, on the island of Sumatra, the impacts of environmental destruction became painfully visible in 2006. Widespread flooding and landslides, intensified by rampant oil palm expansion, displaced over 42,000 people in Tamiang district. By 2015, Indonesia faced yet another ecological crisis: forest fires raged across Sumatra, Borneo, and New Guinea, consuming thousands of hectares of tropical forests and peatlands. Nearly 100,000 fires were recorded. The haze affected millions, with over 28 million people forced to relocate or suffer through severe respiratory illnesses.

Poverty, deforestation, degrading ecosystems, declining human health, and limited access to sustainable livelihoods—these aren’t just environmental disasters. They are public health emergencies and justice issues. Forest degradation deepens inequality. It harms the poorest and most marginalized communities first—those least responsible and least equipped to recover. This is the context in which Health in Harmony (HIH) and Alam Sehat Lestari (ASRI) began their work.

For decades, villagers living near Gunung Palung National Park in West Kalimantan faced the reality of a brutal tradeoff: to pay for healthcare, they logged trees illegally. The forest was their insurance policy—but every cut eroded the very ecosystem that once protected them. This wasn’t just a deforestation crisis. It was a planetary health crisis: the breakdown of the relationship between human health and ecological systems. Between 2007-2008 HIH and ASRI asked a radically different question—not what law enforcement is needed to protect the forest, but:

“What do you need in order to continue protecting this forest?”

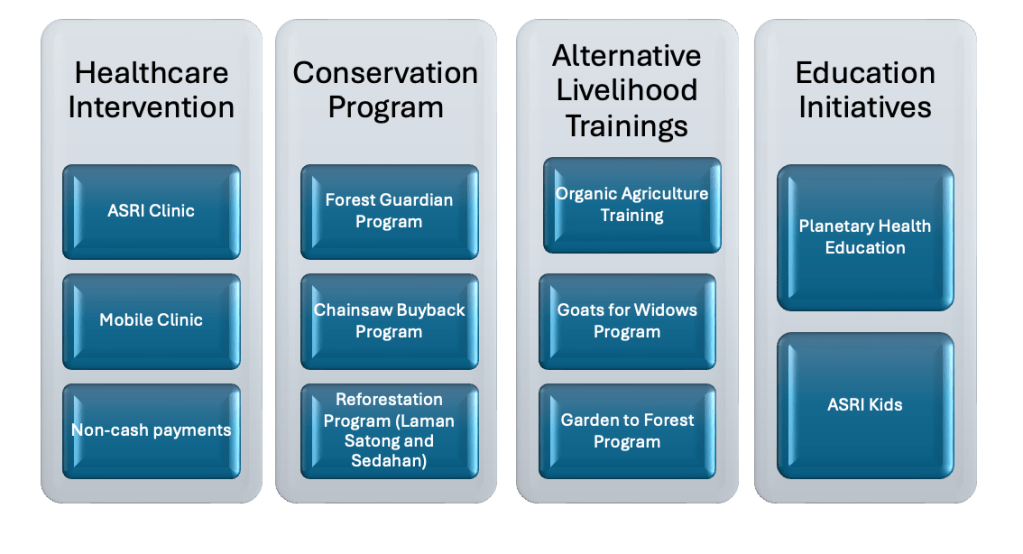

This became the foundation of what we now call Radical Listening—a practice rooted in interbeing, where care for the land and care for people are not separate pursuits but part of one living system. When asked what they needed to protect the forest, the villagers didn’t request payment from carbon credits—instead, they asked for support in finding alternative livelihoods and ways to afford high-quality healthcare. Through listening, a new model emerged—where forest protection was exchanged for access to healthcare, reforestation was repaid in seedlings, and illegal logging rates fell by over 90%. One $5.2 million investment yielded $65 million in carbon protection, but more importantly, it restored the relational fabric between community well-being and ecological stewardship.

One of the most remarkable features of the Health In Harmony and ASRI model is how it rewrites the rules of the system—not with force, but with care.

Instead of using punishment to deter illegal logging, the organizations created an eco-status system. Villages are labeled with different colors—green, yellow, or red—based on the level of logging activity in their area. Each status corresponds to different levels of healthcare benefits. A green status, where there are no signs of forest disturbance in the sub-villages, qualifies villagers for the highest discount at the local clinic—70 percent. A yellow status signals that there is room for improvement, and villagers receive a 50 percent discount. A red status means logging is still prevalent, and only a 30 percent discount applies. The color blue is applied to sub-villages that do not directly border the National Park. ASRI’s clinic provided 50% discount healthcare if no forest disturbance indicators were found during monitoring. Suddenly, protecting the forest isn’t an abstract goal—it’s directly tied to the well-being of loggers and their families. This simple shift rewires the incentive structure, transforming conservation into a community-driven priority.

Designed by HIH and ASRI

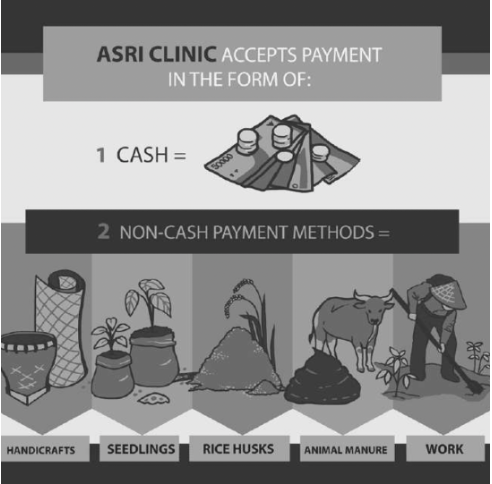

To support villagers who cannot afford to pay for healthcare in cash, ASRI developed a non-cash payment system, accepting a variety of alternative contributions. These include tree seedlings, handicrafts, animal manure, and physical labor—all of which support the restoration of local ecosystems while ensuring healthcare remains accessible to all.

From Cutting Trees to Raising Bees: Pak Amir’s Transition

For years, Pak Amir relied on illegal logging to support his family. He knew it harmed the forest, but like many in his village, he had few options. Logging was risky—but it was a way to survive. Then ASRI came—not with blame, but with questions. Through Radical Listening, they asked what he and his neighbors needed to stop logging. The answer wasn’t punishment—it was support. Pak Amir joined ASRI’s alternative livelihood program and learned beekeeping. He traded his chainsaw for a hive box. Now, instead of cutting trees, Pak Amir raises bees. He earns income from honey, protects the forest that protects his bees, and shares knowledge with others in his community. Today, he owns 100 hives across four locations, and he sells honey to his neighbors, friends, and visitors, making up to 1.5 million rupiah per month.

Through ASRI’s program, he has been able to both pay for his children’s education and preserve the forest for his grandchildren to enjoy one day. His livelihood no longer depends on extraction, but on regeneration. This is what planetary health looks like in practice: restoring balance between people and ecosystems across generations. It reminds us that when we invest in community-led solutions, we aren’t just protecting the forest—we’re protecting futures.

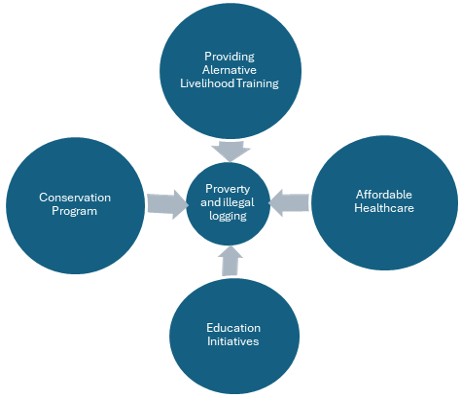

Holistic Health-Conservation Project Design

Holistic project design matters because the crises we face—climate change, biodiversity loss, and public health breakdown—are not separate problems. They are symptoms of a deeper imbalance in how we relate to nature, to each other, and to the systems we inhabit. Planetary health reminds us that human well-being and ecological integrity are inseparable. Healthcare, livelihoods, education, and conservation—these are not competing goals—they are interdependent systems that must be designed together. A clinic in the rainforest, a beekeeping training, or a chance to speak and be heard—these may seem small. But when woven together through systems thinking, they become powerful leverage points for transformation. Holistic design doesn’t just respond to symptoms—it works with complexity, honors relationships, and helps entire systems begin to heal.

Laman Satong: Where the Forest Returned

In the early days of ASRI’s work in West Kalimantan, the villages of Laman Satong and Sedahan had already lost much of their forest cover. Years of illegal logging—driven by poverty and the urgent need to survive—had stripped the landscape. Forests that once buffered rivers and sheltered orangutans were cut down. What followed was land conversion: forest cleared for fields, the soil left exposed and brittle, biodiversity slipping into silence. Eventually, even the fields were abandoned due to declining soil fertility. Before reforestation began, the land was dominated by bushes, ferns, and a few hardy pioneer species such as Macaranga, Vitex, and Bellucia—remnants of resilience in a deeply disrupted ecosystem.

But something remarkable happened in Laman Satong and Sedahan.

In 2009, ASRI established a long-term partnership with local communities and GNPN authorities to restore degraded lowland and peat swamp forests in Laman Satong and Sedahan. This restoration area connects fragmented forest patches, creating wildlife corridors that provide essential habitats for endangered species, such as the Borneo orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus spp).

Reforestation in Laman Satong and Sedahan was not just about planting trees—it was about restoring a living system, and doing so with the community at its heart. More than 30 native species were used in the effort, with a planting composition of 50% hardwoods—like ironwood, Shorea, Syzygium, and Palaquium—and 50% fruit trees, including durian, jackfruit (Artocarpus), and stinky bean. These species were carefully selected for their ability to thrive in mineral soils and for their ecological and cultural value.

Local communities led every stage of the process. They collected wildings from the forest, seeded new plants, and sold seedlings directly to ASRI. Others cared for them in community-run nurseries, even producing eco-polybags as sustainable growing media. Community members also handled logistics, prepared planting plots, and planted the seedlings by hand.

Importantly, their role didn’t end there. Residents have been central to ongoing maintenance and monitoring, checking seedling growth every six months for up to two years, and helping with forest fire mitigation in reforestation zones. In this way, reforestation became not just an intervention—but a shared commitment to healing the land, grounded in both science and trust. Over 200,000 trees were planted by local hands—each one an act of healing.

Over time, the forest began to respond.

As the seedlings took root and the canopy slowly closed, signs of biodiversity returned to Laman Satong and Sedahan. Birds like hornbills and drongos reappeared. Small mammals began foraging among the undergrowth. A once-silent landscape began to hum again with life. Species that had vanished from sight were seen once more—drawn back by habitat, shade, and the slow rebuilding of an ecological web.For villagers who had once cleared these lands out of necessity, the return of wildlife became a point of quiet pride. Some began to notice not only more animals and insects, but cleaner water, cooler air, and even better harvests nearby. Forests that were once seen as resources to be extracted were now have their more-than-human kins returning home.

Reforestation here wasn’t a corporate offset or a satellite target—it was the result of systems-based restoration, driven by local knowledge, ecological science, and a deep cultural shift from extraction to stewardship. Villagers didn’t just plant trees—they repaired a living system. They brought back biodiversity not as an abstract goal, but as part of their own future. Reforestation in Laman Satong and Sedahan shows us that when ecological restoration is tied to human well-being and when communities are trusted as leaders, forest healing becomes possible.

Reforestation Site in Laman Satong (Tree Nurseries and Firebreaks)

Conclusion: Healing Forests, Healing Futures

The story of Laman Satong and Sedahan is more than a local success—it’s a blueprint for how we must reimagine conservation in the age of planetary crisis. Through radical listening, community co-leadership, and systems thinking, these villages have not only restored their forests—they have restored relationships: between people and land, between livelihoods and ecosystems, between present needs and future generations. As Rusda, the forestry manager at ASRI explained:

“We cannot choose between forest sustainability and human health—both must be achieved together. To find a solution, we must ask those who live it: the community.”

This philosophy is what makes the HIH-ASRI model unique. It does not treat people as recipients or forests as carbon stores. It sees them both as essential, living parts of the same system. And it reminds us that ownership, participation, and trust are not optional—they are foundational.

“Community involvement in every step must be maintained, so they feel ownership of the programs being implemented.”

If we are to face the climate and biodiversity crises with wisdom and compassion, we must build more solutions like this—rooted in listening, designed by communities, and held together by shared responsibility.

“Let’s work together to create a healthy and prosperous community, as well as a sustainable nature!” Rusda Concluded.